Versión en español

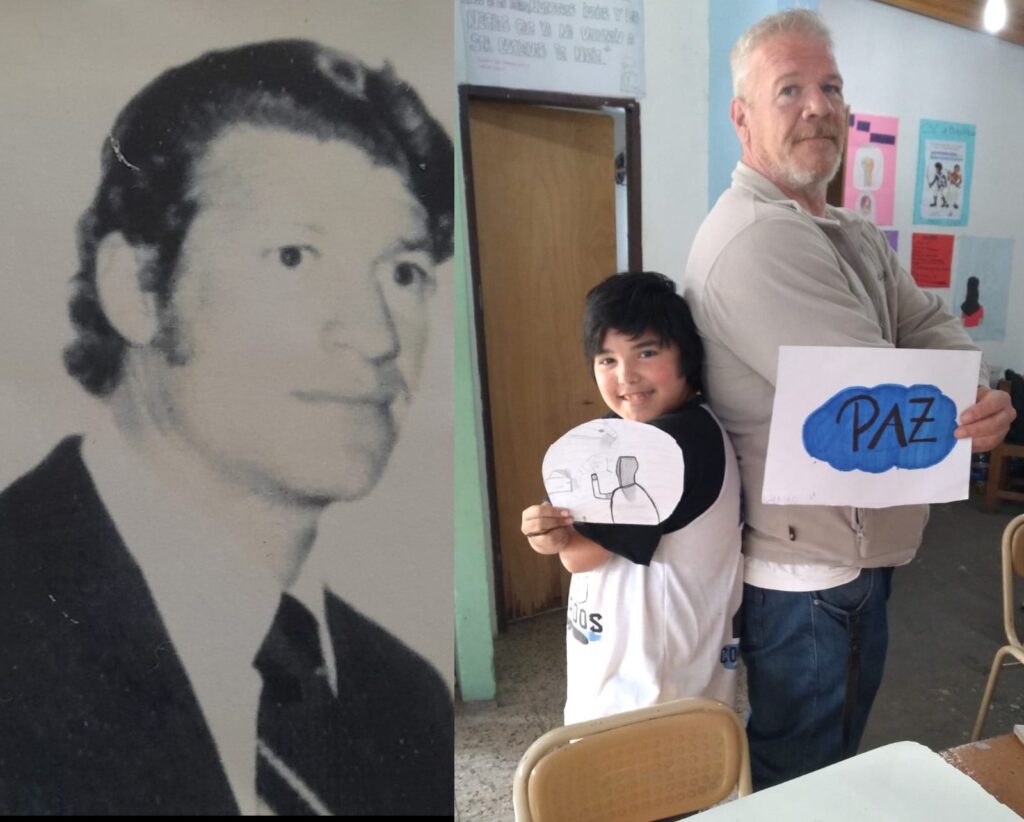

It was a summer. Playing cards with an uncle. Deep into the night. There was a table, cards and glasses of wine. At one point, there were more glasses than cards. And a player accidentally dropped an Ace. «I remember,» said the uncle, «when the military took your old man away.» «I was like WHAT? And there was a scene…», remembers Walter Van Hoof. Years later, there are scenes but they are different, and on the tables there are cards but also posterboards. They belong to his children from the Human Rights workshop at the Socio-Educational Center «La Biblioteca» in Villa Caraza, where Walter (51) continues the work that his father started 45 years ago. Or, if you want to see it that way, where he takes his cards and continues the hand.

Walter Van Hoof , of Dutch ascendance, grew up in a butchers’ family and he was 35 years old when he found out that his father, Rolando Agustín Van Hoof, metalurgic worker and militant at Juventud Trabajadora Peronista [Peronist Worker Youth], had not died in an accident: he was disappeared during the last Argentine civil-military dictatorship.

Without looking for it, he met a young man who asked him if he was active in “H.I.J.O.S.” (Sons and Daughters Against Forgetness and Silence), a Human Rights organization created by the descendants of people who were disappeared by Argentina’s last dictatorship. Before that, he had never protested or participated in defense of Human Rights. “H.I.J.O.S. helps you to see how to carry on with your life,” Walter said. “When they invited me to the first barbecue I said ‘I’m going to go with my car in case it’s boring or I don’t like the atmosphere and I want to come back sooner.’ I stayed until midnight because we chatted so much… it seems that I did feel comfortable,” he recalled.

Van Hoof is sure that interacting with people who suffered similar traumas helped him to understand events of his childhood: for example, why only two friends attended his birthday parties. “H.I.J.O.S. helped me find what I was missing: the story, my story,” said. “H.I.J.O.S. ‘revenge’ is to be happy”, Walter claimed. “H.I.J.O.S. is life, H.I.J.O.S. is not death”, he said.

How is the militancy in “H.I.J.O.S.”?

It’s the nicest thing that happened to me because you start to hear stories of people who lived the same thing as you. It helps you to move forward with certain hard aspects of your life. HIJOS is the most federal Human Rights organization in Argentina because there are “hijos” all over the country. You could say H.I.J.O.S. is already my life, I have been a part of it for more than ten years and met very good people from all political backgrounds.

What aspects of your life has “H.I.J.O.S.” helped you to understand?

One connected the dots. I remember my birthdays as a child during the dictatorship and beginning of democracy, only two boys came and they were brothers and children of disappeared people. The mothers were afraid to bring their children to my birthday, imagine if a patrol came down and took them all away. Thus, we, the hijos, have known what is now called “bullying” all our lives. It was very normal that out of fear they formed groups and left us outside.

How is “H.I.J.O.S.” organized?

“H.I.J.O.S.” of the Province of Buenos Aires meets once a month in different places. Then, at a national level, there are more or less 15 regional meetings and two major meetings per year: one is for delegates and it’s held in a different province each year. Two representatives per region attend this meeting and they define the topics that will be discussed in the general meeting. This latter is held in another province. At the last general meeting had an attendance of more than 200 hijos.

What happened to you when you learnt your true story?

It radically changed my mind because during the 90s I couldn’t understand the protests for Human Rights I saw on TV. Now I’m protesting in the first line. It was a part of me that was missing, I felt like I belonged somewhere else. It’s like I was in a family that wasn’t mine and I felt in the air that there was a lie. Then I began to understand those attacks of overprotection or nerves from my mother. And I think the best thing that could have happened to us as a family was to go to testify. After that I felt ten years younger. I was proud to say that my father was a political activist.

What did you do when your uncle told you your dad had been disappeared by dictatorship?

I started looking for data because I stayed with what he had told me. I spoke with a guy from the Partido Obrero who was studying Law at the National University of Lomas de Zamora and we went to the Civil Registry of Escobar, where the body appeared, to look for the death certificate. There they told us that it was a lie that there were disappeared people in Argentina. We went to the cemetery, to the oldest funeral home in Escobar, posing as workers from the Human Rights Secretary and we asked about my father’s body and, according to them, he was one of the few that appeared because they were cremated in a club behind from the police station. Then we went to the scientific police in Campana and they already knew that we were looking for information about my father, they told us that there was nothing there so we left. Later I found a lot of information thanks to a woman who had a disappeared brother who turned out to be one of my dad’s compañeros. She had a lot of files saved and that’s where I was able to more or less piece together the story.

Do you know why your mom didn’t tell you the truth?

Out of fear. In fact, she was always very overprotective of me and my brother. To this day he is afraid and asks us if we have our IDs when we are in the street. She is terrified [Taking people to police stations for not having their ID was a terror practice during dictatorship].After the elections she was very upset because a lot of things were going through her head.

How did you experience elections?

At first nothing happened to me, now I’m feeling bad. I don’t want to watch television, I don’t want to listen to anything. I try to isolate myself a little, it’s very shocking. We are creating a security protocol, working in the Civil Association to have a legal framework. We are preparing for something we don’t know what it is and hope we never use it.

How would you explain to someone who does not know what political militancy is in Argentina that you belong to an organization that defends Human Rights?

I experienced that when I visited Chile with my compañeros. In that country there are also people with stories similar to ours and we shared many moments. they don’t fully understand Peronismo and I say that it is like death: you never understand it but one day it comes to you (laughs). There is also some of this “inevitability” concerning Human Rights — at some point in life you are going to say “I have a right.” At some point it will be your turn to stand for your rights and that could happen anywhere in the world. Therefore, I think it’s good that in places where Human Rights were violated people create organizations to avoid that happen again. That’s the famous “NUNCA MÁS”. We are the opposite of the “rifle club”, we value life more than anything else.

How do you live your role as a Human Rights teacher for children and adolescents?

The workshop was a challenge because it was something I had never done before. I don’t have children and being with the kids was a challenge and a learning experience, you go and learn with the kids. I am often surprised by how clear they see these issues. Sometimes you bring up a topic that you think may be difficult and it turns out that they see it clearer than you. Youth gives the motivation to always go forward and for more. At this stage of my life it feels great and I think it’s what I was needing.

* Nota producida en el marco del taller English For Journalists dictado por AUNO

SG/JJR